Blogs

#MeToo in Persian Poetry

22 March 2022

(by Asghar Seyed-Gohrab, first published 2017)

#MeToo may be seen as a new phenomenon, but there are many examples in medieval Islamic literature of sexual harassment and women who defend their rights and personal integrity.

Alexander the Great and the unveiled women

The behavior of the American producer and studio owner Harvey Weinstein has rightfully generated a chain of reactions about the way certain men treat women. When I first heard the story, I thought of an anecdote about Alexander the Great, recounted by the Persian poet Nezami from Ganja (d. 1209). In his Alexander Romance, Nezami narrates how Alexander’s soldiers, who have not seen a woman for over a year, arrive at the plains of the Kipchak people in Central Asia and encounter beautiful, unveiled women, busy with their daily lives. They cannot restrain themselves and storm towards the women. Witnessing the commotion in his army, Alexander hurries to the head of the tribe, asking him to cover the women with veils, believing that the men will be less aroused if the women cover themselves. When the leader of the tribe hears this from Alexander, he gives the following answer:

It is not our habit to cover our faces;

Certainly, this is not part of our ways in Kipchak.

If it is your custom to cover faces,

We cover our eyes in our culture. (…)

Instead of damaging the faces of people with a burka,

you should cover your eyes with a veil.

People who cover their faces with a burka,

will neither see the moon nor the sun.

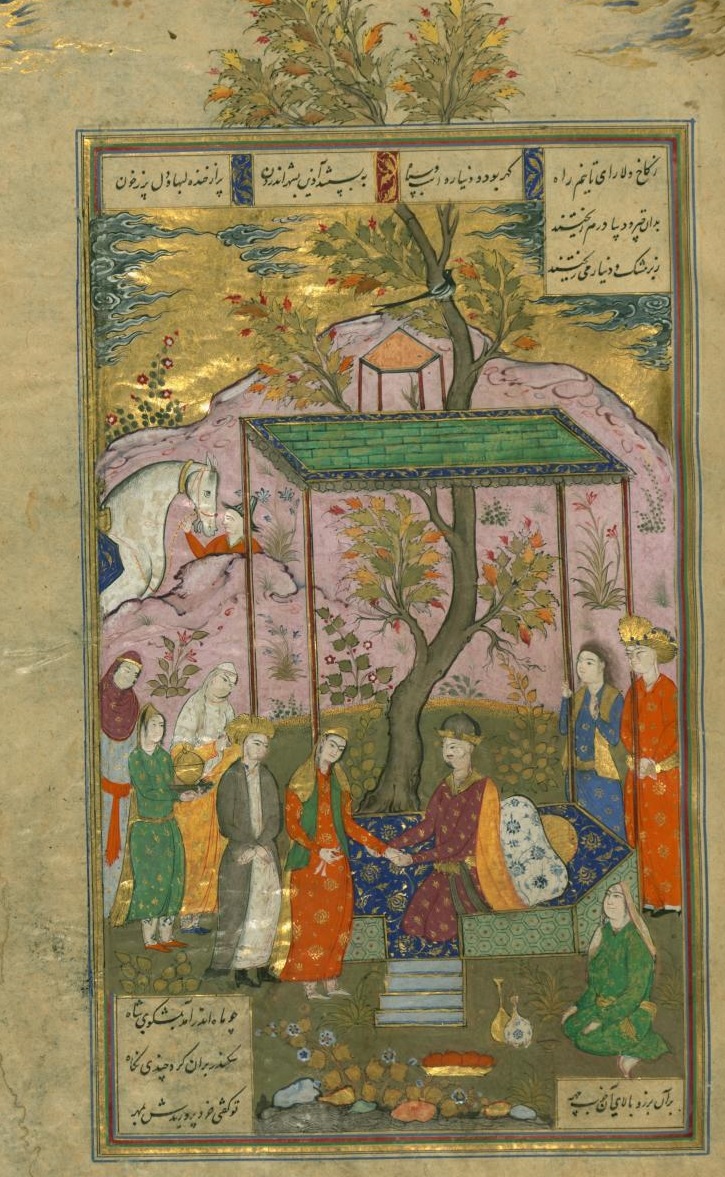

Alexander the Great meets Rushanak, the daughter of Darius. Miniature painting from the Walters manuscript W.602, 1618-1619.

The answer that Nezami places in the mouth of the chief is so topical today in the Islamic world that opponents of dress codes use these powerful verses to argue that instead of instructing women how to dress, men should be held responsible for their own behavior. Nezami is the most feminist medieval Persian poet that I know. In this poem, as in his other epics, women shine both in their moral and physical qualities as well as in their learning. They often teach men a lesson, and if necessary, they even fight men to protect their integrity.

Female self defense in Layla and Majnun

Nezami’s work contains several episodes in which women successfully defend themselves against men who sexually harass them. One example occurs in the romance of Layla and Majnun, which inspired Eric Clapton to write his best-selling album, usually known by its title number “Layla”. In this romance, Majnun is madly in love with Layla but her parents reject him and marry her off to a wealthy Arab, against her wishes. When her wedded husband Ibn Salam approaches her, Layla slaps him in the face with such force that he falls unconscious to the floor. She then asks him not to approach her again because she is still deeply in love with Majnun:

Layla beat him such a blow,

That he fell senseless like a dead man.

She said: “If you do this one more time,

You will be a fugitive from yourself and from me.

I swear by God, who has adorned

My lover Majnun by his divine creation

That your selfish intentions cannot be fulfilled through me

Even if your blade may shed my blood.”

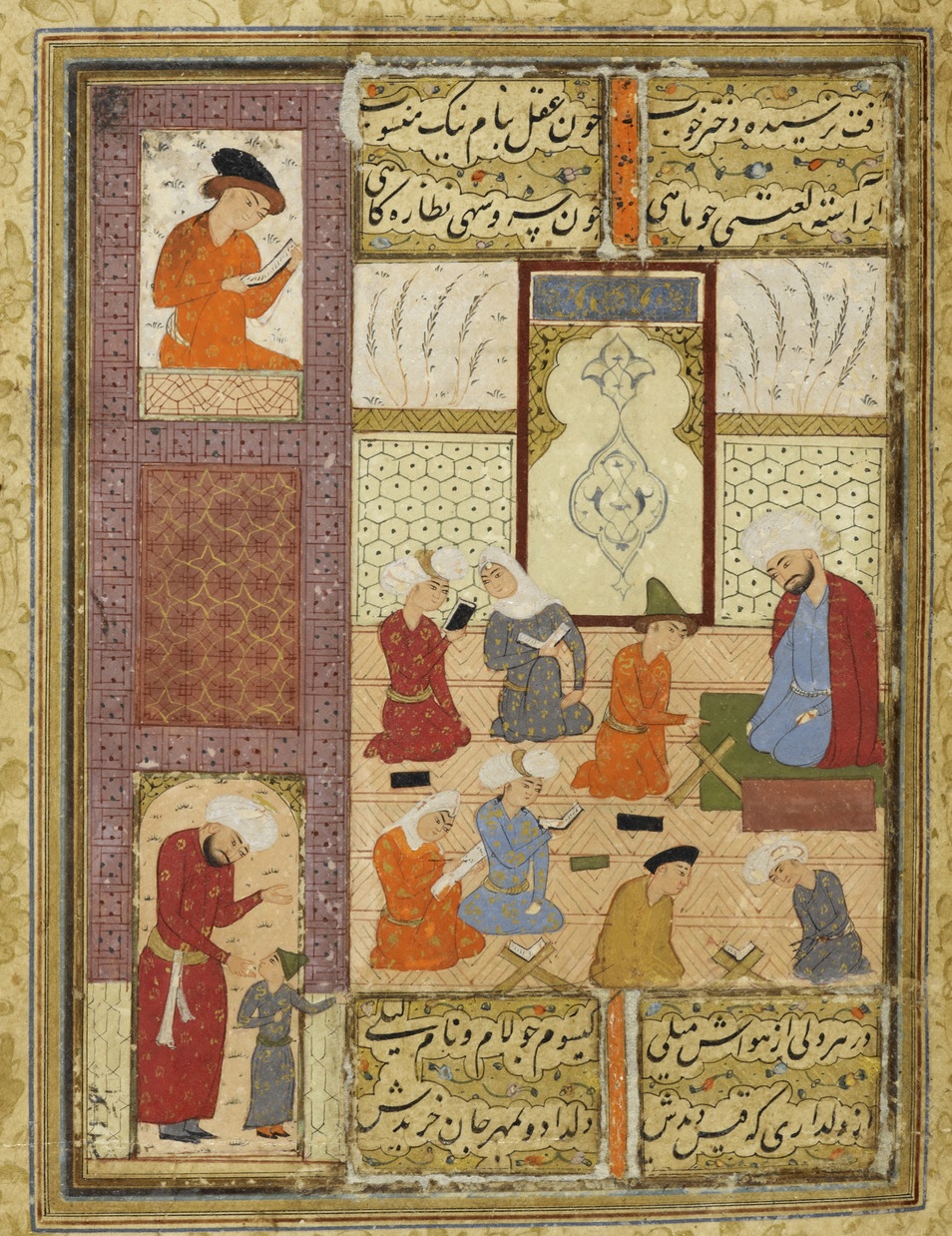

Layla and Majnun at school. Miniature painting from the Majalis al-‘Ushshaq (“The Assemblies of the Lovers”), 1590-1600.

Nezami broaches a sensitive subject in this episode. According to Islamic law, Layla is Ibn Salam’s legal wife and has to fulfill the sexual needs of her husband. The fact that Layla, while married, is in love with another man makes the situation even more poignant. Nezami creates much tension in this scene, questioning religious and social norms. Nezami gives no answer, but both the negative descriptions of Ibn Salam and the fact that Layla slaps him in this way, exhibit his partiality to the female perspective. To emphasize the fruitlessness of Ibn Salam’s attempts to win over Layla, she is compared to a lamp and the moon, and her husband to a wind:

On seeing that shining lamp

He hurried like the wind to find a solution,

Unaware that, even if he was to offer a treasure,

A lamp will never agree with the wind.

As he returned to his native land from his journey,

He yearned for union with that moon, Layla.

It was as if he had forgotten this saying:

“No one shall embrace the moon.”

Nezami, the author of this splendid romance, does not allow a marital rape. Ibn Salam respects the physical space of his wife Layla and finally dies from frustration.

Poetry against the patriarchy

Nezami’s significance as a feminist medieval poet becomes evident when we look at other cases of sexual harassment in Persian literature. One example is the work of Zhale Qaem-Maqami (1883-1946), whose poetry is a personal document depicting her life at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century in Iran. Married against her will at the age of 15 to a man in his forties, Zhale runs away from her husband within two years, leaving behind her son. She was reunited with her son after 26 years. Her poetry is remarkable for dealing with a wide range of subjects related to women such as pregnancy, miscarriage, and women’s position in a patriarchal society. She is very critical of her husband and depicts him in several of her poems as a shallow person offering no respect or love. The following passages may also point to marital rape, as her husband approaches her in the middle of the night. What is unique is how eloquently Zhale describes how she has to submit her body to her husband’s desires against her will, and how such an intercourse results in undesired pregnancy, and how she sees herself as a mother. This is a very strong poem, depicting the fate of women married against their will:

I saw that one night, out of no heart’s desire,

I agreed with my body to yield to my husband

He placed a burden in my heart

which I’ve described in various ways.

Because of this heavy burden,

I made my narrow waist like the canopy of an elm tree,

Not with love, but with instinct I nourished him

Not forming him with discerning intellect.

I placed him to my breast, gave him milk, and then left:

a dog does the same as I did.

The sad conclusion she draws in another poem exhibits her incredibly painful experiences with her undesired husband:

I wished that girls might not show their heads

from their mother’s wombs.

Or if they couldn’t remain in the womb,

that they might surrender their souls in the womb,

or that they might extend their hands to demand

the rights denied to them.

#MeToo may be seen as a new phenomenon, but there are many examples in literature of sexual harassment. Fortunately there are men such as Nezami who consciously and strongly condemn any unsolicited sexual relationship outside of a loving embrace.

Further reading:

Asghar Seyed-Gohrab, (2014) Mirror of Dew: The Poetry of Ālam-Tāj Zhāle Qā’em-Maqāmi, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, ILEX Foundation Series.

Asghar Seyed-Gohrab, (2003) Laylī and Majnūūn: Love, Madness and Mystic Longing in Nezāmi’s Epic Romance, Leiden / Boston: E.J. Brill.

© Asghar Seyed-Gohrab and Beyond Sharia ERC Project, 2022. Any unlicensed use of this blog without written permission from the author and Beyond Sharia ERC Project is prohibited. Any use of this blog should give full credit to Asghar Seyed-Gohrab and Beyond Sharia ERC Project.

Previously published at #MeToo in Persian poetry – Leiden Medievalists Blog

Leave a Reply